Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

The German hydrogen backbone without customers or suppliers—a pipeline from nowhere to nowhere—is real steel in the ground, pressurized and defended as inevitable, yet it is being built for an energy system that does not need it. That claim sounds provocative until the energy flows are laid out in full. When Germany’s energy system is examined through three complete Sankey diagrams, the case for a national hydrogen energy backbone dissolves into a problem of mismatched assumptions rather than missing ambition. The backbone exists because hydrogen is treated as an energy carrier of first resort and assumes maintenance of commodity industrial use cases in Germany, instead of maintenance of high-value add skilled industry. The flows show it is, at best, a niche material input and, at worst, a costly detour.

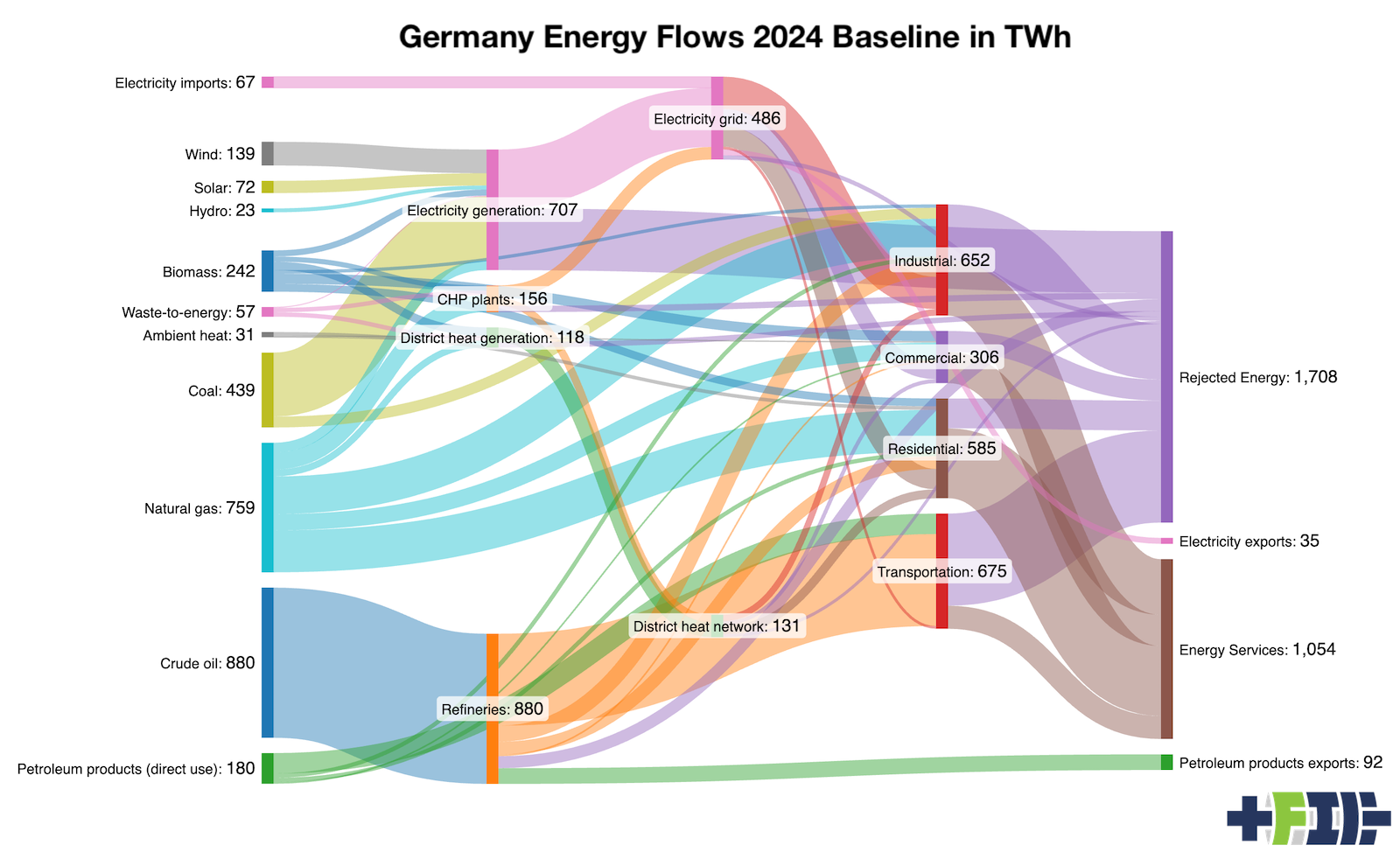

The first Sankey describes Germany’s energy system as it actually operated in 2024. Primary energy inputs totaled roughly 2,900 TWh. Fossil fuels dominated, with oil, gas, and coal providing the majority of that energy. Electricity generation converted a large share of those fuels into power, rejecting a substantial fraction of energy as heat at power plants and engines. Transport alone rejected more than 500 TWh as waste heat from internal combustion engines. Buildings burned gas and oil directly, rejecting heat through flues and poorly insulated envelopes. Industry combined fuel combustion, process heat, and electricity with large losses at each step. The key feature of this Sankey is not the size of any single flow but the width of the rejected energy stream. Well over half of primary energy never delivered useful services.

This first diagram matters because it establishes what decarbonization must change. It is not only about swapping fuels. It is about collapsing loss pathways. The as-is Sankey shows that Germany’s climate problem is largely the efficiency problem embedded in combustion and thermal conversion. Any pathway that preserves those conversion chains will struggle, regardless of how green the upstream fuel appears.

The second Sankey represents a fully electrified, renewables-based end state that delivers the same energy services as 2024 without fossil fuels. Primary energy falls sharply because wind, solar, hydro, geothermal, and ambient heat replace combustion. Electricity becomes the dominant energy carrier. Heat pumps move ambient heat into buildings and low temperature industrial processes with coefficients of performance around 3, meaning 1 kWh of electricity delivers roughly 3 kWh of heat. Transport shifts to battery electric vehicles where roughly 80% of electrical input becomes motion instead of 20% for gasoline. Scrap-based electric arc furnaces dominate steelmaking, with some biomethane direct reduction and import of green iron from iron ore and renewables rich jurisdictions like Australia, Brazil and Sweden. Direct electric heating covers high temperature processes where possible.

In this Sankey, total energy services remain constant at about 1,050 TWh. Residential services remain around 410 TWh, commercial around 183 TWh, industrial around 326 TWh, and transport around 135 TWh. What changes is the rejected energy. It collapses from more than 1,200 TWh to well under 400 TWh. The electricity grid expands, imports and exports rise to smooth variability, but the system becomes simpler. There are fewer conversion steps, fewer places to lose energy, and fewer assets that must be sized for peak thermal output. This diagram already meets Germany’s climate goals without hydrogen playing a material role as an energy carrier.

Germany’s hydrogen strategy-era projections assumed total domestic demand of roughly 110–130 TWh across refining, petrochemicals, ammonia, steel, transport, power generation, and e-fuels, but a realistic end-state assessment collapses that figure to perhaps 4–14 TWh, likely closer to the bottom end of that range. Oil refining demand of 25–30 TWh disappears entirely as fuel refining declines. Hydrogen used directly or through e-fuels, together projected at 25–40 TWh, are eliminated as direct electrification dominates. Domestic steel, once assumed to require close to 30 TWh, falls to zero as scrap availability, electric arc furnaces, and imported clean iron units displace hydrogen-based direct reduction, with any residual reduction more likely to rely on biomethane before hydrogen. Power generation shrinks from a projected 10–20 TWh to at most 0–1 TWh as a form of limited capacity insurance rather than a material energy source, but realistically this is better served by biomass to biomethane running in existing gas generation units maintained for the purpose.

What remains is largely petrochemicals, perhaps 4–8 TWh for hydrogenation and purification where hydrogen is chemically unavoidable, and a small residual of domestic ammonia production in niche cases, possibly up to 5 TWh, with imports of commodities such as green ammonia, iron and methanol covering most needs. The result is an order-of-magnitude gap between the hydrogen volumes Germany planned its backbone around and the volumes its industrial system is likely to require, underscoring how infrastructure sizing drifted far beyond realistic demand.

The third Sankey introduces hydrogen into the already decarbonized system. This is deliberate. Hydrogen here is not replacing fossil fuels. It is replacing efficient electrification. About 98 TWh of hydrogen is inserted at the point of use, excluding refinery demand and buildings. Producing that hydrogen requires about 152 TWh of additional electricity at current electrolyzer efficiencies. Electrolysis alone rejects roughly 54 TWh. Hydrogen then flows into industrial feedstocks, transport, e-fuels, and power generation.

For industrial feedstocks, hydrogen works as intended. Petrochemicals, ammonia, and some steel processes need hydrogen as a material input. In the Sankey, roughly 54 TWh flows into industrial feedstocks and passes directly into energy services with no additional rejected energy. This is the narrow case where hydrogen makes sense, assuming it is green and if the hydrogen is cheap, which will not be the case in Germany. It is not an energy carrier here. It is a molecule needed for chemistry. In each case, the precursor commodity feedstocks hydrogen is used to manufacture are much more cheaply made elsewhere and transported as bulk commodities to Germany as raw iron ore, oil and natural gas are today.

Elsewhere, the losses stack quickly. Hydrogen to power flows through fuel cells at around 60% efficiency. From roughly 22 TWh of wind and solar electricity converted into 14 TWh of hydrogen, only about 8 TWh ultimately returns to the grid. The rest is rejected. E-fuels fare worse. Hydrogen combined with captured CO2 through Fischer-Tropsch or similar pathways delivers around 40% of the hydrogen energy as liquid fuel. Combustion in engines then converts roughly 20% of that into motion. The Sankey shows this clearly. Hydrogen is turned into electricity, then into fuel, then into heat, with rejected energy at every step.

In the electrified Sankey, transport takes about 132 TWh of electricity plus 25 TWh of biomass-derived biofuels for aviation and shipping to deliver 135 TWh of transport services, with about 22 TWh rejected. In the hydrogen-maximalist Sankey, electricity is diverted to electrolysis, hydrogen is compressed and transported, then converted back into electricity or burned in engines. The same 135 TWh of transport services now requires far more primary energy and produces more rejected energy. Nothing is gained except compatibility with legacy fueling concepts.

Power generation from hydrogen is similar. Hydrogen is framed as backup, but the Sankey shows it as an expensive loop. Wind and solar generate electricity. Electricity produces hydrogen. Hydrogen produces electricity. Each step sheds energy. If backup is required, direct grid reinforcement, demand response, storage, or interconnection all preserve more of the original energy. Hydrogen backup only becomes attractive if one assumes that electricity cannot be trusted, which contradicts the premise of the electrified system.

Producing 98 TWh of hydrogen at the point of use requires a scale of infrastructure that is easy to underestimate when discussed in abstract tonnages. At an electrolyzer efficiency of roughly 65% on a lower heating value basis, that hydrogen output implies about 150 TWh of dedicated electricity input each year. Supplying that electricity with a 3:1 wind to solar split requires about 40–45 GW of wind and 35–40 GW of solar under German capacity factors (~30% wind, ~11% solar). Those generators then feed an electrolyzer fleet of roughly 30 to 35 GW, depending on assumed utilization, with realistic operation closer to 4,000 to 4,500 full load hours per year because electrolyzers must follow variable renewable output unless further overbuilding is accepted.

Beyond generation and electrolysis, the system also requires hydrogen compression, drying, and power electronics, large scale storage to bridge seasonal mismatches between production and use on the order of 10 to 15 TWh in salt caverns, smaller volumes of pressurized storage for daily balancing and distribution, and a dedicated hydrogen transport network. In Germany’s own planning this backbone runs close to 9,000 km, largely repurposed from gas pipelines but still requiring new compressors, valves, monitoring systems, and materials upgrades.

On the demand side, hydrogen use in power generation implies fuel cells or turbines sized for several gigawatts of peak capacity despite low annual utilization, while transport applications require vehicle tanks, refueling stations, and safety systems distinct from the electricity grid they displace. Taken together, manufacturing 98 TWh of hydrogen is not a marginal add-on to a renewables system but a parallel energy infrastructure layered on top of wind, solar, and grids that already deliver the same services more directly. In an upcoming article I’ll try to quantify the extra cost and time it would take to build this unneeded infrastructure.

The comparison across the three Sankeys is instructive. Energy services, the actually useful energy to the economy, are identical in all three. What changes is the width of the rejected energy stream and the complexity of the system. The hydrogen-maximalist Sankey has more boxes, more arrows, and a thicker rejected energy band than the renewables-only Sankey. That thickness represents real electrons generated, paid for, and discarded. Complexity is not resilience in this case, it’s just complexity.

This is where the hydrogen backbone narrative runs into trouble. A national hydrogen backbone assumes large, continuous hydrogen flows as an energy carrier. The Sankeys show that once the system is electrified, those flows are not needed. Industrial feedstocks require limited, localized hydrogen delivery. E-fuels and hydrogen transport displace more efficient solutions. Hydrogen to power reintroduces losses that electrification removed. The backbone is sized for a system that never appears in the physics.

This does not mean hydrogen disappears. It means hydrogen returns to its proper scale. A few TWh for feedstocks. Targeted pipelines connecting producers to specific users. None of this requires a pressurized national energy backbone designed to move hundreds of TWh.

The value of the Sankey diagrams is not rhetorical. They impose accounting discipline. They force every promise to pass through physics. When that is done, the hydrogen backbone looks less like a missing link and more like an artifact of path dependence from gas infrastructure and industrial habit. The steel may already be in the ground, but the energy system it assumes is not one Germany needs to build.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy

cleantechnica.com

#Pressurized #Steel #Missing #Demand #Germanys #Hydrogen #Backbone #Energy #Flows