Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

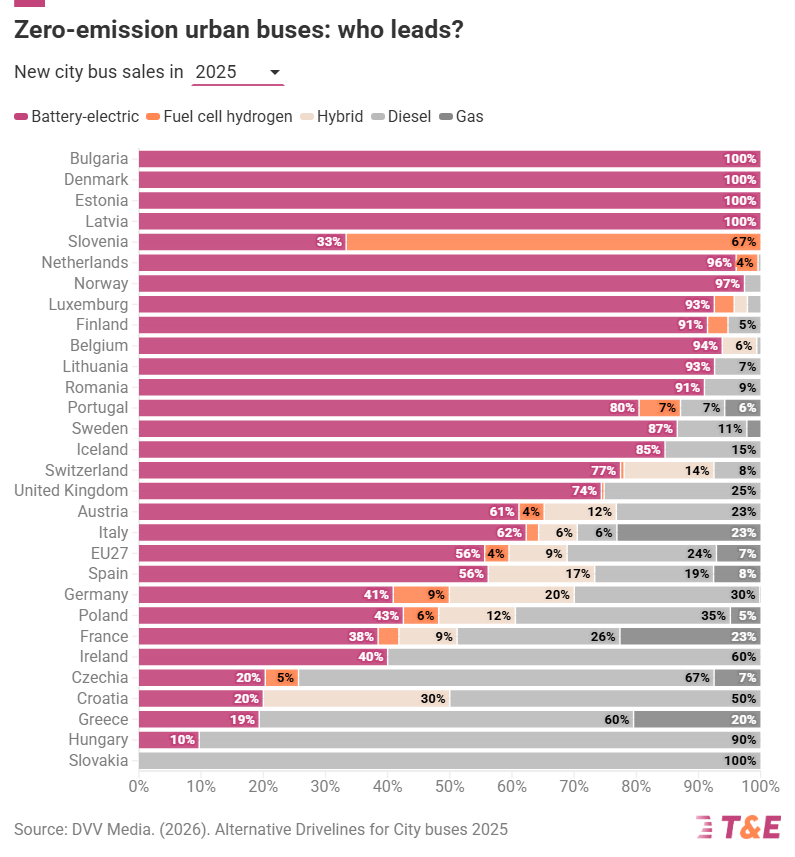

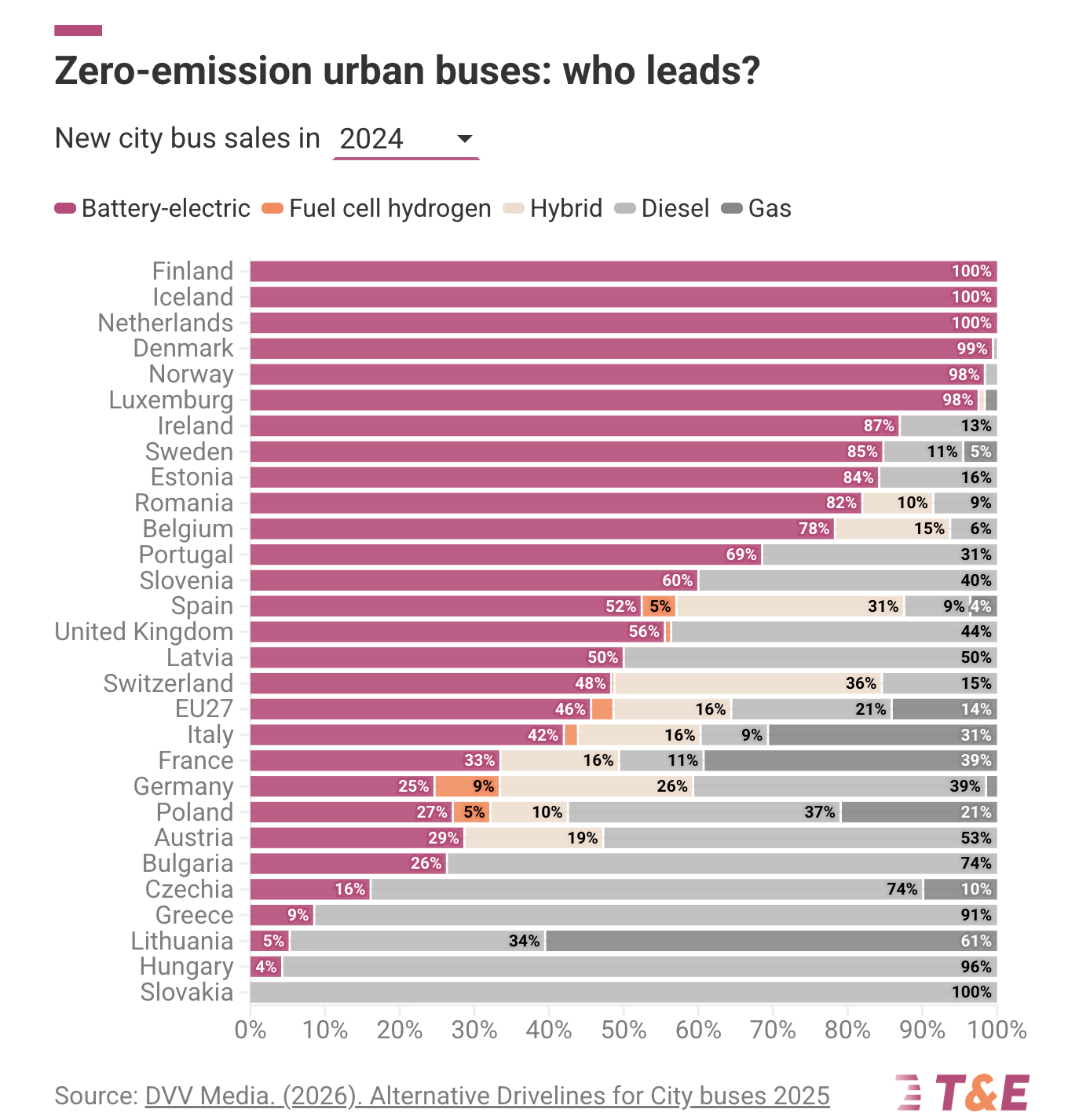

Transport & Environment’s latest European city bus market report glossed in an article in CleanTechnica caught my attention for a reason that may not be obvious at first glance. Battery-electric buses now dominate new city bus registrations across the EU, and vastly ahead of schedule. That is the headline, and there’s a lot to celebrate with that. But buried in the country breakdown is something that looks contradictory. Germany is still at roughly 9% fuel cell bus share in 2024 and 2025. The EU as a whole is around 4%. As hydrogen buses have struggled on cost, reliability, and infrastructure complexity, why are so many still appearing in the data? The answer lies in denominators, procurement lag, and one very large country clearing a backlog of decisions made two to three years ago.

Start with the law of small numbers. Slovenia appears in the T&E chart as a striking outlier in 2025, with hydrogen making up a large share of its purchases. But Slovenia’s total bus market is small. If a country buys 30 city buses in a year and 20 of them are hydrogen, that is 67%. If it buys 15 and 10 are hydrogen, that is also 67%. If it buys six and four are hydrogen, that’s 67% too. A handful of vehicles can swing percentages dramatically. Without looking at absolute volumes, the chart can imply a surge that does not exist in real terms. Slovenia is a useful reminder that percentages without denominators distort perception. The underlying absolute numbers are in a proprietary T&E data set and presumably in their €550 report that I chose not to purchase. A publicly available chart of absolute numbers by country would have been a useful addition.

Now move to the Netherlands, which offers a clearer case study because volumes are meaningful and policy is explicit. In the early 2020s, the Netherlands had hydrogen shares approaching 20% in some years. It was an early leader in zero-emission buses and experimented with both battery-electric and fuel cell fleets. It built refueling depots and deployed hydrogen buses in multiple concessions. Then fleet experience accumulated. Reliability challenges, refueling logistics, and high operating costs became evident. One region decommissioned its hydrogen fleet and refueling entirely. Multiple Dutch transit authorities publicly stated that future procurement would be battery-electric only. The Netherlands is now effectively at 100% zero-emission in new bus tenders, and those zero-emission buses are clearly stated as battery-electric.

Yet in 2025, the Netherlands still shows roughly 4% fuel cell buses in T&E’s dataset. That looks inconsistent with agency statements. If the country registered about 1,090 new buses in 2025 and 4% were hydrogen, that implies roughly 44 fuel cell buses. That number is consistent with residual deliveries from awards made in 2023 or earlier, plus concession transfers and administrative re-registrations of existing hydrogen fleets. Concession documents from 2023 and 2024 required new operators to take over existing hydrogen buses and refueling assets. If a concession changes hands and 20 hydrogen buses move between operators, registration data can reflect that movement in the year of transfer. It’s possible that’s showing up as an artifact skewing T&E’s data set. The Netherlands provides a clean narrative arc. It moved from roughly 20% hydrogen share during early enthusiasm to battery-electric dominance after fleet experience. The remaining 4% in 2025 is a tail, not a pivot back to hydrogen.

At the EU level, the numbers are skewed by Germany. Germany is the largest city bus market in the EU and the largest hydrogen bus market. If Germany is at 9% fuel cell share in and sells 1,200 city buses in a year—my best estimate from the public data available to me—, that is around 108 hydrogen buses, consistent with earlier years’ anouncement. Smaller countries can show higher percentages, but their volumes are too low to move the EU aggregate. Germany’s 9% is what holds the EU average around 4%. Remove Germany from the equation and the EU hydrogen share would fall sharply.

The data for 2024 registered fuel cell buses in Germany is revealing. 9% of buses where hydrogen electric in that year, with only 25% battery electric buses being registered. Between 2024 and 2025, battery electric leapt up to 41%, while hydrogen plateaued at 9%. Germany clearly starting figuring out that battery electric was the winning drive train during the procurement window that led to 2025 deliveries.

The key question is whether Germany’s 9% is a steady state or a trailing indicator. Publicly visible procurement data suggests the latter. In 2022 and 2023, there was a wave of hydrogen bus awards across Germany. DB Regio Bus announced a framework covering 60 hydrogen buses in early 2023. Rebus Rostock ordered 52 hydrogen buses in 2023, supported by federal funding. Duisburg’s DVG awarded a contract for 25 hydrogen buses in mid-2023, with deliveries extending into 2025. Krefeld and other operators placed orders in the 10 to 30 bus range. Add those together and 2023 alone accounts for well over 130 hydrogen buses from a handful of large buyers.

| Year | Operator / Region | Buses | OEM | Announcement Year | Stated Delivery Window |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | DB Regio Bus | 60 | CaetanoBus / Toyota | 2023 | Deliveries beginning 2024 onward |

| 2023 | Rebus Rostock (Mecklenburg-Vorpommern) | 52 | Solaris | 2023 | Delivered through 2024–early 2025 |

| 2023 | DVG Duisburg (NRW) | 25 | Solaris | July 2023 | 12m buses 2024, articulated mid-2025 |

| 2023 | SWK Mobil Krefeld (NRW) | ~15 | Solaris | Oct 2023 | Deliveries through May 2025 |

| 2024 | Ruhrbahn Essen (NRW) | 19 | Solaris | Jan 2024 | Deliveries 2024–2025 |

| 2024 | REVG Kerpen (NRW) | 26 | Solaris | Aug 2024 | Remaining deliveries in 2025 |

| 2024 | RVK Cologne Region (NRW) | 20 firm (+20 option) | Solaris | Mar 2024 | Deliveries beginning 2024, extending into 2025 |

| 2024 | Cottbus / Spree-Neiße | 46 | Wrightbus | Apr 2024 | Gradual deployment in 2025 |

| 2024 | Saarbahn Saarbrücken | 28 | Wrightbus | 2024 | Deliveries starting 2024 |

| 2024 | Rheinbahn Düsseldorf (NRW) | 10 | Solaris | 2024 | Delivery in 2025 |

| 2024 | LNVG Groß-Gerau (Hesse) | 23 | Solaris | Jan 2024 | Articulated units mid-2025 |

| 2025 | WestVerkehr (NRW) | 12 | Wrightbus | 2025 reporting | Deliveries in 2025 (order secured earlier) |

Announcements of EU fuel cell bus awards by author

Those 2023 awards translated into 2024 and 2025 deliveries. Duisburg’s buses entered service in 2024 and 2025. Rostock’s fleet was incorporated into operations by early 2025. These deliveries appear in 2024 and 2025 registration data, reinforcing the 9% share. But they are the outcome of decisions made when hydrogen enthusiasm and federal support were at a high point.

In 2024, hydrogen awards did not disappear. Ruhrbahn in Essen ordered 19 hydrogen buses in early 2024 with deliveries scheduled through 2025. REVG Kerpen ordered 26 hydrogen buses in 2024 with deliveries extending into 2025. RVK in the Cologne region expanded its hydrogen fleet again in 2024. Cottbus and Saarbrücken announced hydrogen orders from Wrightbus in 2024, including batches of 28 and 46 buses. Even a conservative tally of publicly visible 2024 awards reaches well over 120 buses. That does not look like a collapse year. It looks like the last strong year of ordering.

The 2025 picture is different. Publicly visible new hydrogen bus awards in 2025 are almost nonexistent compared with 2024. The only example I could find is WestVerkehr’s order of 12 hydrogen buses, but that order traces back to commitments made in 2024 and at least some deliveries reported in 2025. That does not prove that orders have fallen off a cliff, but it strongly suggests it. Cities continue to announce awards for battery electric fleets, and there’s no evidence of abatement of that. T&E should attempt to project the trajectory’s of buses. They have proprietary data sets and access to data that would enable them to do the analysis.

Procurement timelines matter. A typical cycle runs from funding approval to tender publication to award to delivery over 18 to 30 months. If enthusiasm and funding peaked in 2022 and 2023, awards would cluster in 2023 and 2024. Deliveries and registrations would cluster in 2024 and 2025. If new awards slow in 2025, the impact would not show up in registration shares until 2026 and 2027. The 9% hydrogen share in Germany in 2024 and 2025 can be consistent with a slowdown in new awards, because it reflects earlier decisions working through the system.

Germany will have the longest and largest hangover because it placed the largest orders. If Germany awarded roughly 130 hydrogen buses in 2023 and another 120 or more in 2024 among major operators, that is over 250 buses feeding into 2024 and 2025 deliveries. Even if 2025 awards fall to a few dozen nationwide, the delivery pipeline will take time to empty. The 9% plateau may represent the crest of deliveries rather than the crest of enthusiasm.

The Netherlands offers a glimpse of what comes next. It tested hydrogen at scale, reached double-digit shares, and then pivoted to battery-electric only tenders after accumulating operational experience. Its 2025 hydrogen share appears to be the residual tail of earlier awards and concession re-registration mechanics. Germany is on a larger scale and has deeper hydrogen ecosystem commitments, so the tail will be longer. But even in Germany, hydrogen remains under 10% of new city bus registrations and has likely peaked. It is not a dominant technology. It is a minority technology clearing a backlog of decisions made in a different policy moment. Germany will undoubtedly follow in the Netherlands tire tracks, with agencies announcing more fleet abandonments, refueling decommissioning and doubling down on battery electric.

Arguably, Germany’s ongoing Gruppendenken around hydrogen has contributed to there poor ranking in terms of acquiring battery electric buses. When they are only at 41% and other major European countries are at 75% and higher, they are distinctly lagging, and hydrogen buses suck of procurement cycles, money and effort that would have gone a lot further with battery electric buses.

If publicly visible hydrogen bus awards in Germany remain low in 2025 and 2026, the registration data in 2026 and 2027 will likely reflect that. The EU is already at peak fuel cell bus deliveries in my opinion based on this analysis. The current plateau is the last high point before decline, driven by the long procurement lag between political enthusiasm and vehicles entering service.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy

cleantechnica.com

#Peak #Fuel #Cell #Bus #Deliveries #Occurred