Industries | The Big Take

Almost every day, an oil tanker arrives off the coast of Guyana to pick up a cargo that could reach a buyer practically anywhere on the planet. The stream of shipments is all the more remarkable because just a few years ago, the country didn’t pump a single barrel.

On the other side of the globe at ports in the United Arab Emirates, which has been exporting since the 1960s, there’s also a constant flow of vessels pulling in to load oil. OPEC’s third-largest producer sent the most crude overseas in years last month.

Tanker Traffic to Guyana’s Offshore Oil Production Area Up Sixfold Since 2021

In just four years Guyana has boosted crude exports to nearly 1 million barrels a day, overtaking neighboring Venezuela

Source: Vessel tracking data compiled by Bloomberg, Google Earth

Together, the two countries offer some of the clearest signs of an oil market facing a major glut. Old and new producers alike are ramping up output as sanctioned barrels from Russia search for buyers, putting a record 1.3 billion barrels of crude on the world’s oceans. Benchmark oil prices are heading for their biggest annual loss since the pandemic, while US gasoline at the pump is less than $3 a gallon for the first time since 2021.

The drop is good news for consumers and the politicians who’ve made a point of addressing their cost-of-living concerns, including US President Donald Trump. But it’s also an economic threat to some of the largest producers, like Russia and Saudi Arabia. Oil is as cheap as it was about a decade ago, without adjusting for inflation.

A floating production and storage vessel in Brazil’s Buzios field. The country’s output hit a record this year. Photographer: Dado Galdieri/Bloomberg

Virtually all of the world’s biggest traders see the oil market in a state of oversupply early next year — the only question is by how much. The International Energy Agency estimates that output could exceed consumption by around 3.8 million barrels a day in 2026. Many traders predict smaller numbers than that, but storage levels are still expected to grow.

When that happens, oil prices usually fall. Global benchmark Brent crude is down 20% this year to trade near $60 a barrel. Trafigura, one of the world’s top commodities traders, says oil could be in the $50s through the middle of the year before recovering into the end of 2026.

“It’s a market where everybody agrees what’s going on,” Ben Luckock, global head of oil at the firm, said in an interview. “Prices should be lower, but they can’t be because there’s a war going on in Ukraine still.”

The oil market remains sensitive to geopolitical conflicts that could send futures soaring on any given day. A Ukraine-Russia ceasefire agreement, which could add even more Russian barrels to the market if sanctions are eased, remains elusive. Tensions between the US and Venezuela have escalated, with Trump ordering a blockade of sanctioned oil tankers to and from the South American country. A rapprochement or regime change could initially send prices up but ultimately bring more of that supply to market.

Any sustained price drop next year will be because of the scale of the supply additions that are emerging — fast outpacing uneven consumption growth. Brent crude hasn’t averaged below $60 a barrel for a full year since 2020, and before that the last time it did so was in 2017.

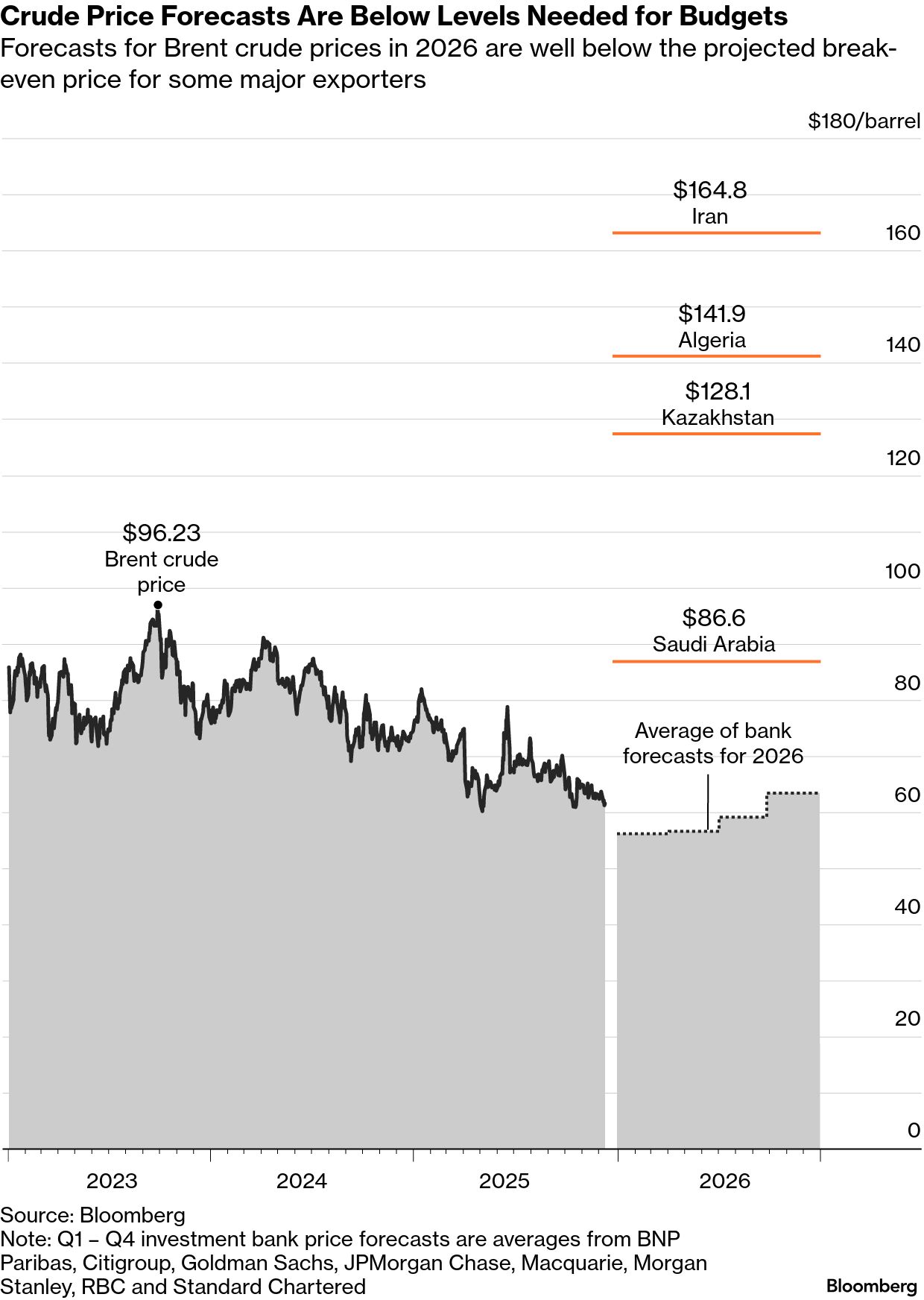

Crude Price Forecasts Are Below Levels Needed for Budgets

Forecasts for Brent crude prices in 2026 are well below the projected break-even price for some major exporters

Note: Q1 – Q4 investment bank price forecasts are averages from BNP Paribas, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Macquarie, Morgan Stanley, RBC and Standard Chartered Source: Bloomberg

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies, led by Saudi Arabia and Russia, have been steadily lifting output since early this year. Brazil pumped a new high of 4 million barrels a day in October, while prices in Canada are near the weakest since March as production mounts. A shale boom in Argentina has helped buoy South American output and China now pumps roughly as many barrels as OPEC giant Iraq.

In the US, where higher production is a pillar of President Trump’s energy agenda, total oil output is forecast to hit a fresh record this year and hover near that level next year. Crude prices on the Gulf Coast, home to the nation’s largest storage tank farm, refining hub and crude-exporting area, are flashing signs of oversupply.

Liberty Lift Solutions LLC pumpjacks near Crane, Texas, the heart of the Permian Basin that’s helped propel US production to a record.

Photographer: Justin Hamel/Bloomberg

“If you leave Russia aside, the rest of the key contributors for the supply growth next year are all on track to deliver what the market is expecting as consensus,” said Frederic Lasserre, global head of research at commodity trader Gunvor Group.

Even sanctioned oil producers are maintaining robust flows, for now. The US has designated hundreds of ships, individuals and companies as falling under its sanctions on Iran, Venezuela and Russia. Still, shipments from the Persian Gulf country, often hidden from plain sight by vessels switching off their satellite transponders, are on course for their highest annual average since 2018.

In Venezuela, volumes were heading for their biggest year since 2019 prior to the recent US blockade and Russia just shipped the most oil in a week since it invaded Ukraine.

Moscow’s barrels continue to find willing buyers in India and China, who collectively import over $1 billion of crude a day and hoover up the supplies to shield consumers from inflation. Russian oil is arriving at Indian ports with the biggest discounts since 2023, according to Argus Media, reducing a giant import bill that acts as a drag on the rupee.

Rising exports from OPEC and non-OPEC producers mean more oil is in transit or waiting to be sold as producers seek out willing buyers for their cargoes, according to Muyu Xu, senior crude oil analyst at Kpler.

“The growing oil-on-water levels point to a supply glut,” she said.

The drop in Brent futures — which traded at more than $80 in the early days of January 2025 — is lowering fuel costs for consumers. UK gasoline and diesel prices are heading for their lowest annual average since 2021.

In the US, the national average is down to around $2.90 a gallon, compared with a peak of more than $5 a gallon in 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine, according to the American Automobile Association. That’s a boon for Trump, who repeatedly promised to lower gasoline prices during his election campaign last year as US consumers remain troubled by the stubbornly high cost of living.

The decline in prices at the pump is “the equivalent of a very major tax cut,” he said Dec. 9.

The economic benefit of lower gas prices shows up almost immediately at filling stations. When drivers spend less at the pump, they usually spend more on snacks, coffee or other convenience store items when paying, according to Eric Blomgren, executive director of the New Jersey Gasoline, C-Store, Automotive Association.

Gas prices in Dallas, Texas, earlier this year — nationwide prices are below $3 a gallon. Photographer: Shelby Tauber/Bloomberg

If the slide in crude prices continues, it would ultimately put a dent in inflation. A $10 drop in the oil price could shave 0.2 percentage points from the consumer price index in the US, South Korea and Japan next year, according to Bloomberg Economics.

Pennies saved at the pump eventually hit the budgets of producers, though.

Saudi Arabia — which effectively needs crude prices close to $90 a barrel, according to data from the International Monetary Fund — is nearing its highest ever annual level of debt issuance this year. The country is open to canceling some projects in its Vision 2030 program, a multitrillion dollar effort to diversify the economy away from oil with projects like desert ski slopes. Other members of the OPEC+ group, like Algeria, Iran and Kazakhstan, need prices far above $100 to cover government spending.

“What I can say with absolute certainty is this: An excess of oil affects the country and affects prices,” said Diamantino Pedro Azevedo, minister of mineral resources for Angola. “This country depends heavily on oil — I don’t say that with pleasure, but it’s the reality.”

With oil falling, OPEC+ last month said it will pause further production increases during the first quarter of 2026. Delegates have privately reiterated it’s the best move while they assess an uncertain market picture and said it’s too early for the group to consider output cutbacks next year. Several are skeptical the projected glut will actually materialize, with forecasts from the group’s Vienna-based secretariat pointing to only a modest surplus in the first half of 2026.

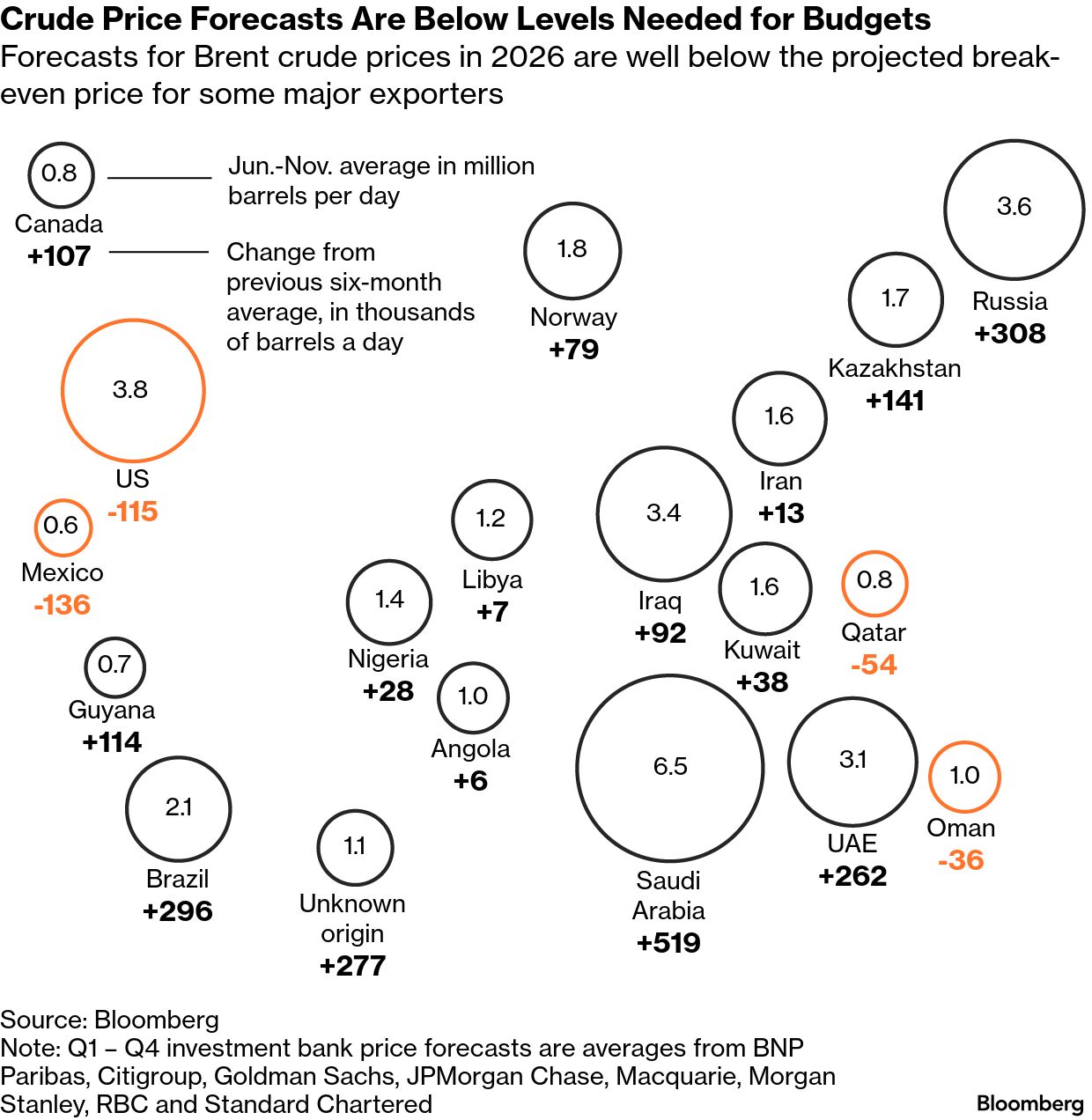

Crude Price Forecasts Are Below Levels Needed for Budgets

Forecasts for Brent crude prices in 2026 are well below the projected break-even price for some major exporters

Note: Q1 – Q4 investment bank price forecasts are averages from BNP Paribas, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Macquarie, Morgan Stanley, RBC and Standard Chartered Source: Bloomberg

The world’s largest oil companies are reacting, too. Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp. and ConocoPhillips are laying off about 14,000 employees combined, with profits well below where they were three years ago.

While most US shale producers remain profitable — just — at $60 a barrel, they’re being forced to squeeze suppliers and cut jobs. At the same time, tariffs have increased the cost of essential oilfield equipment such as pipe, drilling gear and generators.

Two Trump-supporting shale executives, who asked not to be identified discussing private conversations, said they’ve tried to back-channel a message to the administration: The lower oil prices go now, the higher they will go later when production slides. And then it will be hard to quickly bring back the workers and equipment needed to grow again.

Still, a greater share of investment is flowing into core oil and natural gas projects — particularly in the US and deepwater fields — suggesting a desire to keep pumping after an IEA warning earlier this year that spending will be needed to match the rate of production declines from fields as they age.

The Deer Park Complex oil refinery and petrochemical plant, owned by Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), near Houston, Texas. Photographer: Mark Felix/Bloomberg

US shale producers are forging ahead with production plans as technological advancements in drilling allow them to pump more crude for every dollar spent. Diamondback Energy Inc., Coterra Energy Inc. and Ovintiv Inc. last month announced plans to raise output slightly for this year or 2026 despite oil prices falling close to the threshold needed for many US shale wells to break even.

Oil companies “have to choose between sustaining production levels or prioritizing returns,” said Greg Sharenow, who helps manage nearly $20 billion as head of Pimco’s commodity portfolio management team. “That choice will matter a lot to how quickly the market rebalances.”

Ultimately, low oil prices tend to solve themselves by forcing producers to curb output and adding incentives to consume more. Trafigura’s Luckock said if Brent is in the $50s in the spring and the dollar is weaker, it could prove an attractive time to buy for countries that need oil. Torbjorn Kjus, chief economist at Aker BP ASA, said his company remains optimistic in the medium-term as demand continues to rise and supply growth slows in 2027 and beyond.

Demand growth, which has been increasingly hard to predict, also remains a key variable that could either swell or curb the glut. While electric vehicle growth is affecting Chinese transportation demand, gasoline consumption in Europe is soaring and traders and analysts say that demand in emerging markets — where statistics are particularly opaque — is also holding up.

So far, prices haven’t fallen further, in part because stockpiles at key pricing hubs remain historically tight.

Demand to fill storage on land in hubs like the Caribbean and South Africa is low for now, people involved in those markets said, in part because the oil futures curve doesn’t currently make it profitable to do so. Inventories at Cushing, Oklahoma — where US futures are priced — are the lowest for the time of year since 2007.

In contrast, stockpiles in China — propelled by buying for emergency reserves — hit the highest level on record last month at just over 1.2 billion barrels, according to OilX data.

This year will also leave a lesson for those expecting lower prices: The path downward is rarely a straight line. Direct conflict breaking out between Iran and Israel, US sanctions on Russia’s two largest oil producers and the prospect of American strikes on Venezuela have all led to brief jumps in oil that often wrong-footed traders.

“It’s one of the trickiest years ever, not because of volatility but because of unpredictability of headlines,” said Sebastien Willems, chief trading officer at AB Commodities. “You don’t know when the next tweet is coming, and most importantly you don’t know when the reverse is coming.”

But as 2026 gets going and production continues to ramp up, most in the market see a wall of supply on the way.

“I’ve never seen a consensus as large as what we’ve seen, I would say the last three, four months on the balances,” Kjus said. “It’s like an iceberg floating against us.”

— With assistance from Archie Hunter, Kari Lundgren, Mitchell Ferman, Paul Burkhardt, Candido Mendes, Yongchang Chin, Lucia Kassai, Ben Bartenstein, Jack Wittels, Grant Smith, Fiona Macdonald, Kevin Crowley, David Wethe, Rakesh Sharma, Devika Krishna Kumar, Priyanjana Bengani

More On Bloomberg

www.bloomberg.com

#Oil #Prices #Set #Pushed #Global #Glut