Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Dijon is a useful hydrogen transportation case study because it was serious, early, and well funded. This was not a symbolic pilot. The city committed real capital, built infrastructure, signed supply agreements, and intended to operate hydrogen vehicles at scale across buses, refuse trucks, and light municipal fleets. The intention was coherent. The outcome was not and they’ve announced a major reduction and change in their hydrogen plans, as well as a pivot to battery electric. They made the announcement at one of the traditional times for announcements of complete and utter failures, at the end of the week just before Christmas, hoping no one would notice. There’s been a rash of quiet announcements of hydrogen failures in the past week for this reason.

The original hydrogen plan in Dijon rested on two linked ideas. The first was local production of hydrogen by electrolysis. The second was that most of the electricity would come from municipal waste to energy. Roughly 90% of the electricity for electrolysis was planned to come from the waste incinerator—something which caught my eye immediately in its announcement—with the remaining 10% from local renewable electricity. The hydrogen would fuel buses, refuse collection trucks, and a smaller number of light vehicles. The promise was local energy, circularity, and low emissions.

The problem is that electrolysis multiplies the carbon intensity of electricity. At about 55 kWh of electricity per kg of hydrogen, every gram of CO2 per kWh becomes 55 grams per kg of hydrogen. Municipal waste to energy in Europe typically sits around 700 to 900 gCO2e per kWh on an attributional basis once plastics and fossil carbon in waste are counted. Using a mid value of 790 gCO2e per kWh, the electricity alone would produce about 43 kgCO2e per kg of hydrogen before any losses. Adding 5% to 10% hydrogen leakage using a GWP20 of about 37 raises that to roughly 45 to 47 kgCO2e per kg of hydrogen delivered. That is before compression, storage losses, or station energy use.

For a 12 m city bus in Dijon, I assumed a duty cycle of about 60,000 km per year. Real world hydrogen bus consumption from European demonstration fleets averages about 7.7 kg per 100 km. That works out to about 4,620 kg of hydrogen per bus per year. Multiplying by about 45 kgCO2e per kg of hydrogen gives roughly 208 tons of CO2e per bus per year. A conventional diesel bus on the same duty cycle using about 52 L per 100 km consumes about 31,200 L of diesel annually. At 2.68 kgCO2 per L, that is about 83 tons of CO2 per year. The original WtE hydrogen plan would have produced more than double the emissions of diesel buses.

Refuse trucks look similar. A refuse truck in Dijon typically runs about 25,000 km per year. Diesel consumption is extreme due to stop start operation. A mid value of 119 L per 100 km is representative. That results in about 29,750 L of diesel annually and roughly 80 tons of CO2 per truck per year. Hydrogen refuse trucks consume about 14 kg per 100 km. That equals about 3,500 kg of hydrogen annually. Using the same WtE hydrogen emissions factor, each truck would emit about 158 tons of CO2e per year. Again, materially worse than diesel.

Light vehicles make hydrogen look even weaker. A light municipal vehicle at 15,000 km per year and 0.9 kg per 100 km uses about 135 kg of hydrogen annually. Even that small amount results in about 6 tons of CO2e per year on WtE hydrogen. A diesel light vehicle at about 6.7 L per 100 km emits about 3 tons of CO2 per year. Hydrogen doubles emissions in this case.

As an important aside, waste to energy electricity in France typically sits in the range of roughly 700 to 900 gCO2e per kWh once the fossil carbon in plastics and other synthetic materials is counted, while the French grid as a whole averages about 20 to 25 gCO2e per kWh due to its heavy reliance on nuclear and hydro. That is a difference of more than an order of magnitude. Calling waste to energy a climate solution ignores what it actually is. It is a waste disposal system that happens to recover some energy, not an energy system designed to minimize emissions. A significant share of the carbon released comes from single use plastics, which are fossil derived and would have remained largely sequestered for long periods if landfilled rather than combusted. From a climate perspective, burning plastics to generate electricity takes stored fossil carbon and moves it directly into the atmosphere, while avoiding very low carbon grid electricity that already exists in France. That makes waste to energy barely defensible as an energy source and clearly misaligned with decarbonization goals and is another case of Dijon failing miserably to address climate concerns by looking at the actual CO2e emissions of their schemes instead of marketing brochures from equipment sellers.

The vehicle emissions numbers should have meant that the original hydrogen plan was never considered. The emissions profile was fundamentally misaligned with climate goals, even before cost or reliability were considered. This is not a marginal error. It is an order of magnitude problem driven by electricity carbon intensity and the physics of electrolysis.

However, that’s not what happened. They actually went ahead with this. They had ordered and received an electrolyzer from now defunct provider McPhy, and one refueling station of two was constructed, as far as I can tell. The value of that contract was €4.6 million, but it’s unclear how much they paid and if they are going to be able to get any of it back. They had also ordered 27 hydrogen buses from now defunct bus manufacturer Van Hool at €1.25 million per bus, prepaying €800,000 which they are trying to get back from the liquidator, but are of course in a long lineup with their hands out.

They’ve also received 8 hydrogen refuse trucks from two manufacturers, E-Truck and Hyundai, at a cost of €700,000 each, so another €5.6 million committed. The original plan had another 15 light municipal vehicles, but there’s no evidence that they followed through on any acquisition, so presumably haven’t lost any money yet.

The backup plan after the electrolyzer supplier failed and with the pivot is to truck in hydrogen from external suppliers for the 8 refuse trucks. In practice this will be gray hydrogen from steam methane reforming. Plant gate costs are often quoted at €1 to €3 per kg, but mobility hydrogen is never delivered at that price. Compression to 350 bar, tube trailer transport, station capex recovery, maintenance contracts, and low utilization dominate costs. Real pump prices across France and Germany sit between €12 and €15 per kg, with some sites higher, and those are money losing prices for retail outlets at the volumes they are running at, hence the raft of closures.

Using €13 per kg as a median delivered price, aligned with US DOE baselines for delivered and pumped hydrogen costs, the economics shift but the emissions do not improve compared to diesel. Gray hydrogen has about 9.4 kg of direct CO2 emissions per kg at the SMR plant. Adding upstream methane leakage at 1% to 3% and using GWP20 yields another 3 to 8 kgCO2e. Adding hydrogen leakage of 5% to 10% adds about 2 to 4 kgCO2e. Delivered gray hydrogen ends up around 14 to 23 kgCO2e per kg. Using a midpoint of about 19 kgCO2e per kg is reasonable.

At that level, a hydrogen bus emits about 88 tons of CO2e per year, essentially the same as diesel. A hydrogen refuse truck emits about 66 tons, slightly better than diesel. A light vehicle emits about 3 tons, again matching diesel. There is no meaningful climate benefit at fleet scale. Costs remain high. Maintenance complexity remains high.

Cost comparisons explain why some hydrogen use cases appear cheaper than diesel while others do not. A bus using 7.7 kg of hydrogen per 100 km at €13 per kg costs about €100 per 100 km. The same bus using 52 L of diesel per 100 km at €1.68 per L costs about €87 per 100 km. Hydrogen is more expensive. A refuse truck using 14 kg per 100 km costs €182 per 100 km on hydrogen, while diesel at 119 L per 100 km costs about €200 per 100 km. Hydrogen is cheaper in this narrow case because the hydrogen drive train is more efficient for stop start driving, mostly due to the batteries and electric motors. At €15 per kg, hydrogen becomes more expensive again.

The capital cost picture is where hydrogen fails decisively. A battery electric 12 m bus in Europe typically costs between $500,000 and $600,000. The hydrogen fuel cell buses costs $1.25 million. That is a difference of roughly $600,000 to $700,000 per bus before infrastructure. Hydrogen refueling stations cost several million euros even at modest scale, with €4.6 million getting them, in theory, two stations and an electrolyzer. Depot charging for battery buses costs a fraction of that per vehicle. The variance in capital cost alone overwhelms any narrow fuel cost advantage hydrogen might claim in specific duty cycles.

Dijon ultimately pivoted away from hydrogen buses entirely. As of its most recent public statements, the city does not operate hydrogen buses and has abandoned plans to do so. It has chosen battery electric and biodiesel hybrid buses instead. For refuse trucks, Dijon has stated that it will continue with hydrogen vehicles already delivered, but has not announced expansion. The hydrogen station infrastructure remains, but utilization will be extremely low with only 8 refuse trucks of a planned total 209 hydrogen vehicles of the three types. And as I pointed out based on analysis of California’s and Quebec’s refueling station data, the stations are highly likely to be out of service for maintenance for more hours than they are actually pumping hydrogen, as was the case in both of those examples. Maintenance costs will be much higher than those for diesel fuel pumps or battery electric chargers.

The replacement strategy for buses is battery electric combined with HVO renewable diesel hybrids where electrification is believed to not meet the duty requirements for range or steep hills with current technology, although realistically all they have to do is wait a couple of years and they’ll get all the range they need. Alternatively, they could use bog standard in motion charging that’s expanding quickly on the steepest hill sections or the lead up to them and avoid hybridization entirely. The numbers are unambiguous. A battery electric bus using about 1.2 kWh per km consumes about 72,000 kWh per year. France grid electricity averages about 22 gCO2e per kWh. That results in roughly 1.6 tons of CO2e per bus per year. Rounded, that is about 2 tons. Even if charged on waste to energy electricity at 790 gCO2e per kWh, the bus would emit about 57 tons per year, still far below WtE hydrogen and below diesel.

HVO also performs well. Using European waste and residue based HVO with lifecycle intensity around 18 gCO2e per MJ, a diesel bus consuming about 1.1 million MJ per year emits about 20 tons of CO2e. That is a reduction of more than 75% compared to fossil diesel and dramatically better than hydrogen options available to Dijon. These of course will be hybrid electric, and hence lower than that, but a pure energy to energy comparison is suitable.

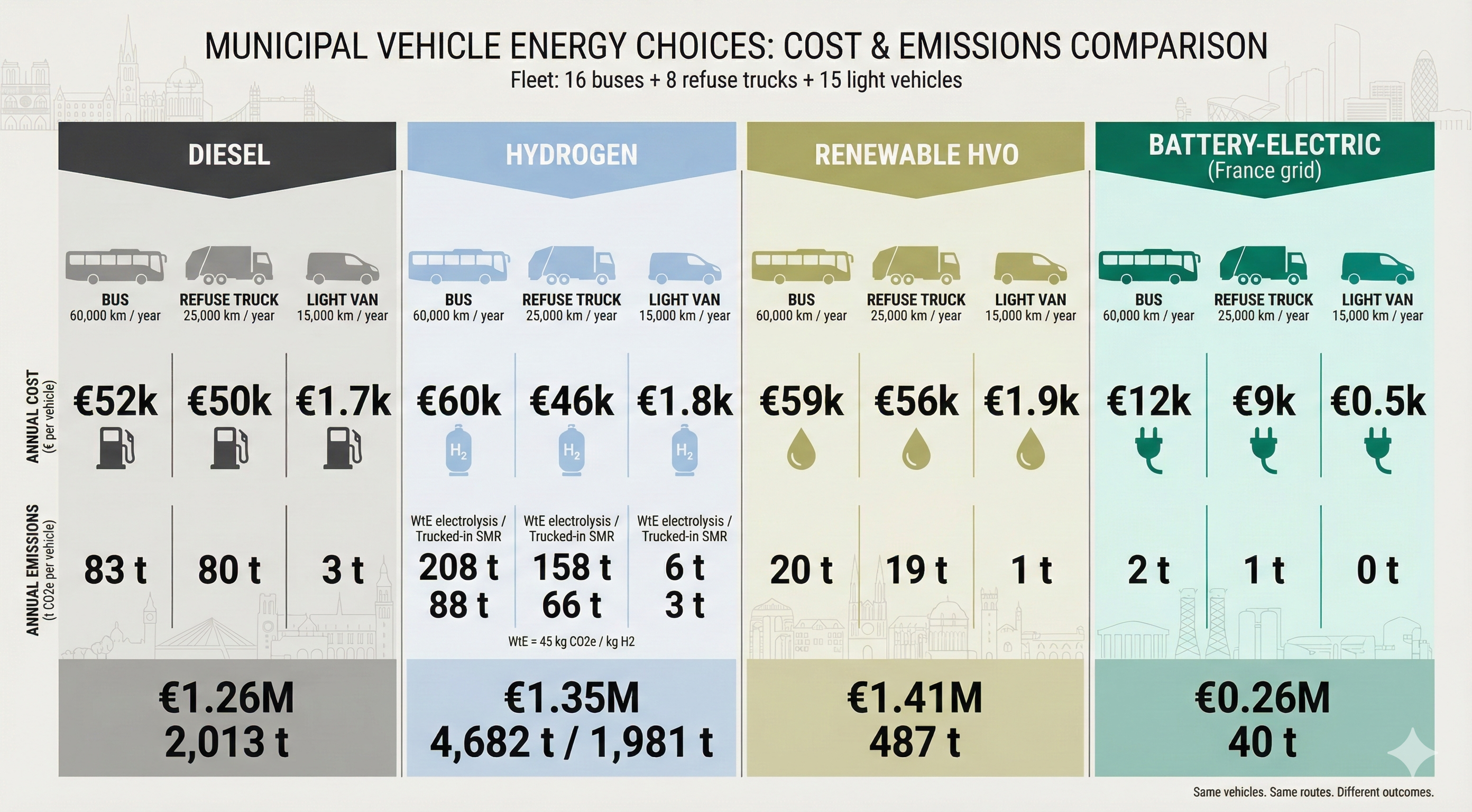

At fleet scale the differences are stark. For a fleet of 16 buses, 8 refuse trucks, and 15 light vehicles, diesel emits about 2,013 tons of CO2 per year. Trucked in gray hydrogen emits about 1,981 tons. WtE hydrogen at 45 kg CO2e per kg H2 would have emitted about 4,682 tons. HVO reduces emissions to about 487 tons. Battery electric vehicles using France grid electricity reduce emissions to about 40 tons. Even charging all BEVs on waste to energy electricity results in about 1,294 tons, still far below WtE hydrogen electrolysis.

Operating costs follow a similar pattern. The full fleet costs about €1.26 million per year on diesel. Hydrogen at €13 per kg costs about €1.17 million. At €15 per kg it costs about €1.35 million. HVO costs about €1.41 million. Battery electric vehicles cost about €260,000 per year in electricity. The fuel savings alone pay for the capital cost difference over a few years.

Maintenance and reliability add further weight. Hydrogen stations require compressors, high pressure storage, leak detection, and frequent inspections. Uptime requirements for municipal fleets are high. When stations fail, vehicles are stranded. I fully expect that the 8 hydrogen refuse trucks will be unable to fulfill their duty cycles, so Dijon better not retire any diesel vehicles from their fleet, increasing maintenance costs again of course. Battery charging infrastructure is simpler, more modular, and benefits from a mature supply chain. HVO requires no new infrastructure at all.

Dijon did not abandon hydrogen because it lacked ambition. It abandoned hydrogen because the technology is flakey, credible vendors who attempt it often fail completely as I’ve pointed out over and over this year with my hydrogen for transportation deathwatch and the costs were eye watering. Emissions would have been higher than diesel and in the new case for the refuse trucks see no benefit at all. Fuel costs were higher than diesel and the other alternatives. Capital requirements were far higher than battery electric. The pivot to battery electric buses and HVO hybrids for remaining diesel fleets delivers lower emissions, lower costs, and lower operational risk. The remaining hydrogen vehicles in refuse deliver no climate benefit and impose ongoing infrastructure costs. That reality is not unique to Dijon. It is a general outcome of physics, economics, and real world operations.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy

cleantechnica.com

#Hydrogen #Cut #Mustard #Dijon