Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

The debate about vehicle weight and road damage shows how quickly a simple idea can gain traction even when the underlying evidence is thin. Commenters often reach for a familiar claim that heavier vehicles must be responsible for increased road wear. The argument sounds reasonable at first glance and it appeals to a basic intuition that more weight should equal more damage.

The trouble is that intuition is a poor guide to pavement engineering. Most modern roads are designed for axle loads far above anything in the light duty fleet. Only the heaviest commercial vehicles push pavements toward their design limits. Cars, crossovers, SUVs, and pickup trucks sit so far below those limits that their differences in mass do not register in most models of pavement fatigue or rutting. The idea that EVs or even the most outsized of US SUVs create meaningful additional road damage because they weigh more does not stand up well when set beside contemporary engineering research.

This came up because I published recently on the disparity between the societal costs of internal combustion and electric vehicles, pointing to OECD and UK data showing that ICE vehicles have roughly three times the societal costs, but that doesn’t mean EVs don’t have costs. Further, I pointed out that gas taxes and similar schemes don’t remotely pay for roads, despite that being their original intent, with typical gas taxes paying only a fifth of the cost of maintaining roads. What pays for roads is general governmental revenue and, where they exist, usage tolls. My proposal was for a rational system of charging owners of vehicles based on distance driven annually, applied to all road vehicles based on societal costs of their use, with ICE vehicle drivers charged three times as much as EVs per kilometer, EV drivers charged too, with some sensible variances for rural vs urban dwellers and the bottom quintile of income earners.

Multiple commenters wanted to add road damage to the list. Because they were commenting in CleanTechnica‘s webpages and on my article, they weren’t attacking EVs, but were clearly thinking of the bloated SUVs and pickups so common in the USA, land yachts that dwarf the largest human, whose grilles often tower as tall as an average height woman. But road damage isn’t caused by heavier personal vehicles.

A lot of the confusion traces back to the Fourth Power Law. It was born from a single experiment in Illinois in the 1950s and has survived far past its useful life. The AASHO Road Test measured how pavements responded to repeated truck passes under controlled conditions. Frost heave damaged the test track during the study and the damage was attributed to the trucks. The statistical analysis itself had problems, including attributing differences in pavement life to axle loads that were not actually responsible for much of what happened. The result was an elegant equation that suggested that road damage increases with the fourth power of axle weight. An equation like that is irresistible. It is simple. It appears quantitative. It has been passed along for decades. The trouble is that it was tied to unique local soil conditions, a narrow range of pavement designs and vehicles that no longer resemble what is on the road today.

Research through the 1980s and later, including the work of David Cebon at Cambridge, who I’ve spoken to at length about this, made the limitations clear. Pavement wear is not governed by a single variable. It is influenced by structural, environmental, and dynamic factors that shift over time. Static axle load is one factor, but real damage is strongly shaped by dynamic tyre forces created by suspension behavior, road surface roughness, tyre design, and vehicle speed. Pavement structure, subgrade strength, temperature, and moisture all change the way layers respond to these loads. Fatigue and rutting accumulate differently under different seasonal conditions.

When engineers model these systems with modern tools, they see that the Fourth Power Law is usually a poor predictor of real pavement life. As Cebon noted in more than one conversation, if the law was accurate, Michigan’s highways would be destroyed every year due to its high legal truck weights. The fact that they are not points to the inadequacy of the simplistic weight-based model.

Michigan is an excellent real-world check on these assumptions. The state allows truck combinations with gross weights up to 164,000 pounds, about 74.4 metric tons, roughly double the common limit for Class 8 trucks elsewhere. If fourth power scaling was correct, its roads would fail at rates that would force constant repaving. That does not occur. Michigan’s experience shows that axle configuration, dynamic load distribution, and pavement design matter far more than the raw gross vehicle weight number. A well designed multi-axle truck spreads loads across the pavement in a way that greatly reduces stress. Michigan’s paved network has issues like any northern state network, but the problems do not look like the catastrophic failures predicted by a pure fourth power model.

Despite these clear warnings, the Fourth Power Law found new life over the last decade as a way to attack EVs. It reappears frequently in online debates, policy opinions, and news commentary. The argument usually runs that EVs are heavier, therefore they must increase road wear, therefore EV owners should pay higher road charges. The problem is that the mass differences between light duty EVs and similar internal combustion vehicles do not produce discernible changes in pavement life. The absolute loads from light-duty vehicles are simply too small. Most road wear comes from heavy trucks, not cars or SUVs. When the same logic is applied to SUVs and pickup trucks rather than EVs, the conclusion is still weak because the difference between a 1800 kilogram crossover and a 2400 kilogram pickup truck is trivial next to the dynamic forces created by a fully loaded semi. Misusing the Fourth Power Law creates a neat talking point, but it does not produce an accurate model of societal cost.

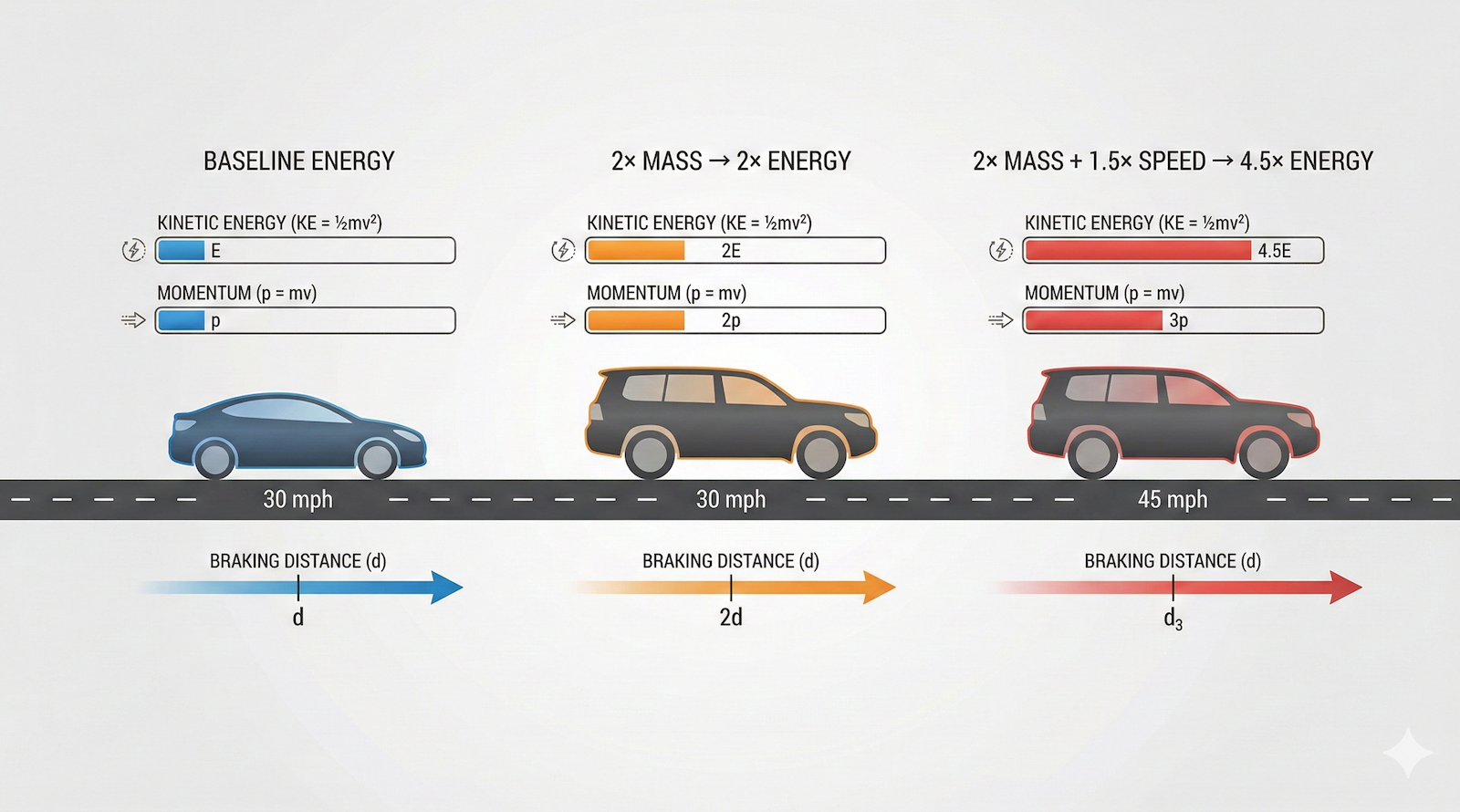

Where weight does matter is in collisions. The physics is unforgiving. Kinetic energy increases with the square of speed. A crash at 40 mph delivers almost twice the energy of a crash at 30 mph. At 50 mph, the energy is about triple. Heavier vehicles carry proportionally more kinetic energy and transfer more of it into whatever they hit. When a tall front end meets a pedestrian, the consequences are far worse than with a lower car, even if the speeds are the same. Visibility issues and longer braking distances compound the risk. Rising SUV and pickup weights are linked with rising pedestrian injuries because the mathematics of energy transfer leave little room for a different result.

The interaction of mass and velocity explains why the risk compounds so quickly. Double the mass and increase the velocity by 50% and the impact energy grows by a factor of about 4.5. That multiplier is not intuitive, which is why many people underestimate the danger of larger and faster vehicles. The same issue appears with acceleration. EVs can reach high speeds quickly. China took this seriously and set a governed default acceleration of five seconds from zero to 100 kph for electric cars, with faster acceleration available only after a conscious user choice. The issue is not the technology. It is the interaction between mass, speed, and human reaction times.

A related issue is the shape of the front end on many SUVs and pickup trucks. High flat grilles strike a person’s torso or head rather than the legs, which removes the possibility of the lower body absorbing some of the impact while the upper body rotates onto the hood. That rotation is what often prevents fatal injuries in collisions with lower sedans. When the leading edge is tall and vertical, the energy is delivered directly into the chest and vital organs. The geometry also increases the likelihood of a person being pushed forward and down rather than lifted, which raises the probability of being run over. These design choices reflect the dubious taste of the owners who like them, but they create real risk in urban environments where pedestrians and cyclists share limited space with large vehicles moving at higher speeds.

If heavier vehicles do not meaningfully damage roads but do create higher collision risks, then the policy answer does not lie in weight-based road usage charges. It lies in managing speed, vehicle geometry, and exposure. Reasonable speed limits that are actually enforced improve safety. Removing emissions loopholes for large SUVs and pickup trucks improves accountability. Vehicle safety tests that include potential impacts on pedestrians and cyclists are important. Better street design reduces conflict points. Traffic-calming reduces the energy of inevitable collisions. More transportation alternatives reduce total vehicle kilometers traveled. These measures align with what traffic safety engineers know about risk rather than what commenters assume about weight.

The conversation about EV weight and societal cost can be more grounded when the distinction between road wear and collision physics is made clear. Roads do not fail because an EV weighs a few hundred kilograms more than an internal combustion car, or when an egregiously oversized SUV or pickup rolls down them. They fail when dynamic heavy vehicle loads, especially on rough pavement, exceed what the pavement structure can absorb. People, by contrast, are injured or killed when the mass and speed of a vehicle deliver more kinetic energy than a human body can survive. Understanding the difference provides a better path for policy and a better foundation for evaluating what the transition to electric mobility truly changes.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy

cleantechnica.com

#Outdated #Engineering #Models #Distort #Todays #Road #Charges #Debate