Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

The German Bundesrat’s recent plea to Brussels to double green hydrogen-base fuel quotas is less a bid to accelerate decarbonization than a request to manufacture demand for an infrastructure program that never made economic sense and had weak demand signals from the start. The upper chamber’s proposal to increase mandated volumes of hydrogen-based fuels undercuts the core principle of market efficiency and makes clear that the issue is no longer whether hydrogen has a role but how to salvage investments already committed.

When a signatory to a project argues that targets need to be expanded because the original targets are too low to justify the assets built, the problem is not insufficient ambition but a flawed economic foundation that never offered competitive fuel costs without permanent subsidies. The Bundesrat framing positions the state as guarantor of user demand rather than letting end users decide based on cost and performance.

Independent fiscal institutions in both France and Germany have already said that hydrogen strategies for transport should be reconsidered because they cost far more than alternatives. France’s national audit office found that replacing fossil fuels with electrolytic hydrogen in transport implies a cost per ton of CO2 avoided on the order of €400 up to €520 when the full chain from renewable electricity through electrolysis, compression, distribution, and vehicle use is accounted for, and that this sits far above the cost outcomes of direct electrification pathways. The French auditors also noted that nearly half of hydrogen subsidies to date went to road transport, a sector where battery electric trucks already demonstrate lower total cost of ownership, and recommended that continued public subsidy use for hydrogen in freight be reevaluated.

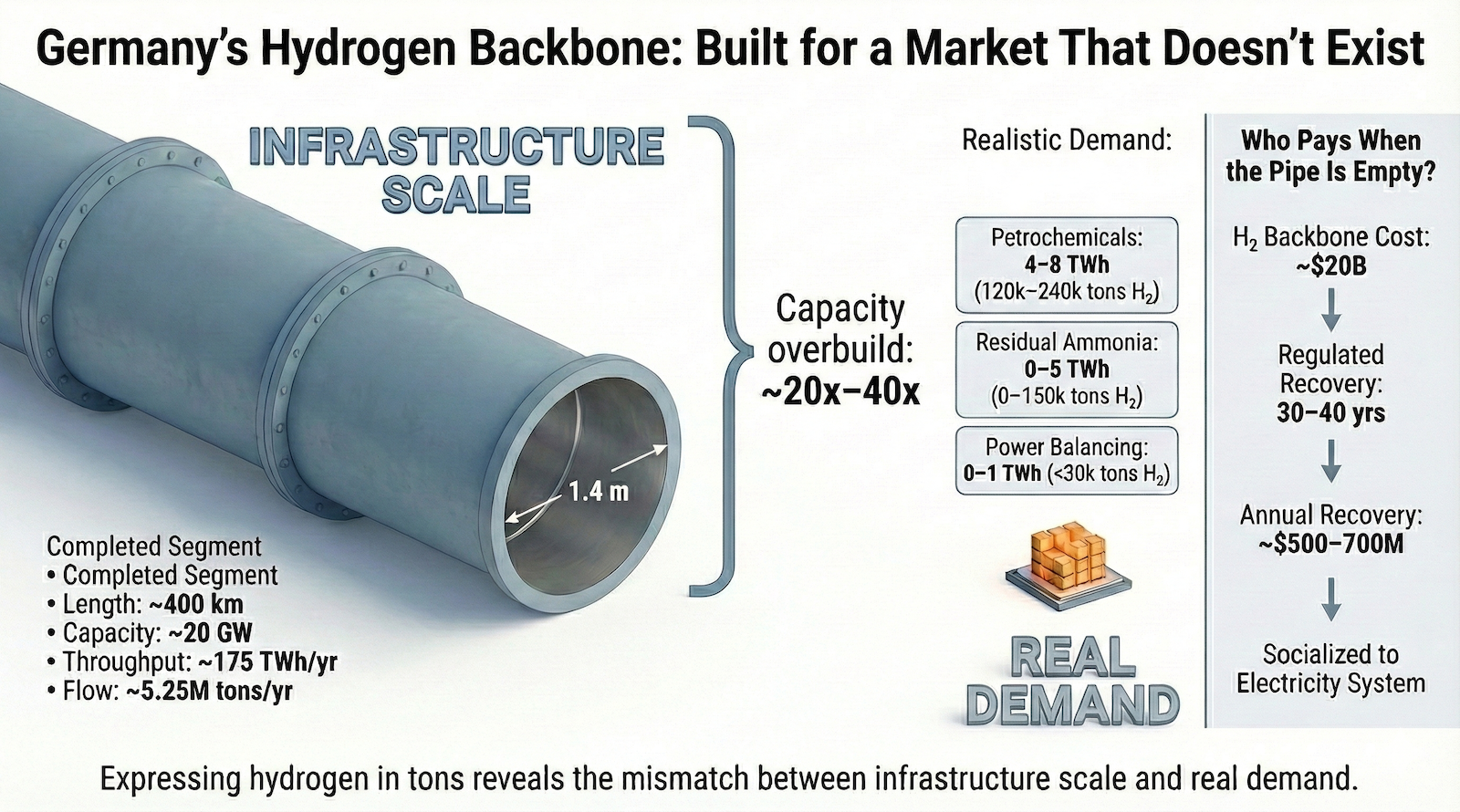

In Germany, the Federal Audit Court’s statutory assessment of the national hydrogen strategy found that both supply and demand for green hydrogen have lagged far behind expectations despite billions in federal funding, and that planned production and import volumes necessary to justify backbone infrastructure remain implausible. The audit showed that steel projects intended to anchor demand have delayed or uncertain timelines, and that planned roles for hydrogen in power generation have been quietly scaled back, leaving core hydrogen offtake assumptions unfulfilled. Pressurizing segments of the national hydrogen network before credible suppliers and committed offtakers existed converts optional infrastructure into active liabilities with operating costs and financing risk. That shift triggers fiscal exposure under Germany’s financing structure, where state-backed loans of up to €24 billion depend on future network utilization for repayment, meaning taxpayers would be exposed to most of the shortfall if demand never arrives.

These institutional warnings, from two of Europe’s most sober fiscal guardians, matter because audit offices do not advocate for technologies; they evaluate whether public money is deployed in ways that respect legal obligations, cost effectiveness, and realistic demand projections. They call attention to the absence of synchronized growth of supply, demand, and infrastructure that was the explicit assumption of the original hydrogen strategy, and they underline that continuing to subsidize an uneconomic pathway is a budgetary risk rather than a climate strategy.

The combined French and German advice aligns with separate recommendations from the joint economic advisory councils of both countries, which concluded that battery electric trucks outperform hydrogen alternatives on total cost and efficiency and that public investment should favor high-power electric charging networks rather than generalized hydrogen refueling infrastructure. This consensus across independent institutions and advisory bodies, each applying different analytical lenses, points toward electrification as a lower cost, lower risk, and higher adoption pathway for decarbonizing road freight.

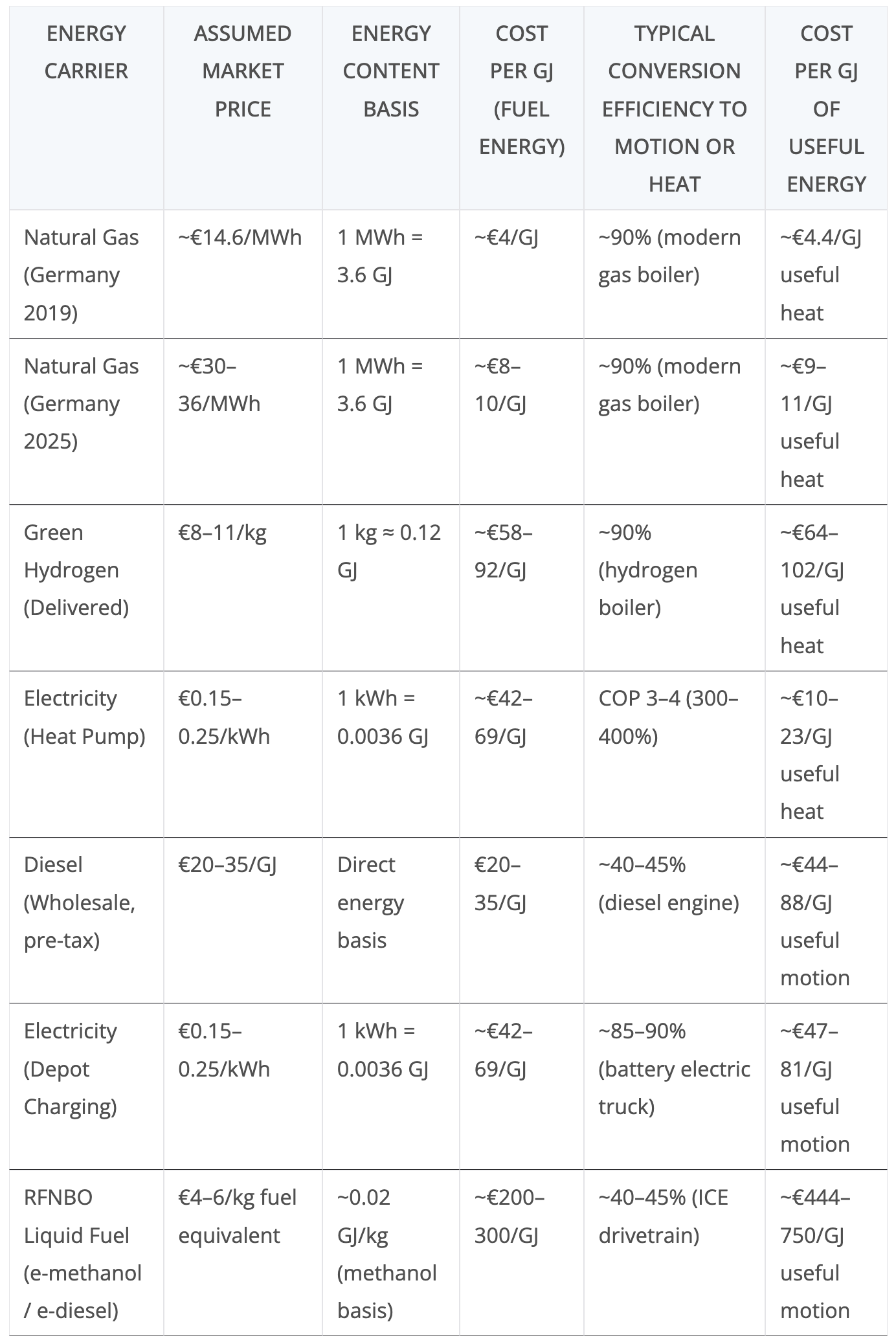

When the numbers are laid out, the cost disparities become unambiguous. Natural gas in Germany historically traded at wholesale hub prices equivalent to roughly €4 per gigajoule in 2019, and post-crisis normal wholesale pricing in 2025 sits in a range around €8 to €10 per gigajoule including carbon pricing under the EU emissions trading system, even though those carbon costs remain below €80 per ton.

In contrast, realistic delivered green hydrogen prices anchored to signed contract and subsidy mechanisms across Europe suggest an implicit cost band closer to €8 to €11 per kilogram delivered to synthesis sites, and when converted to energy units that equates to roughly €58 to €92 per gigajoule. Those figures are three to eight times higher than contemporary natural gas fuel costs and dwarf wholesale electricity costs used for direct electrification.

At typical European retail electricity prices of €0.15 to €0.25 per kWh, a heat pump operating at a seasonal coefficient of performance of 3 to 4 delivers useful heat at roughly €10 to €23 per GJ, which is competitive with natural gas at today’s wholesale levels and far below hydrogen. With ETS2 set to extend carbon pricing to residential and commercial heating fuels, the cost of burning natural gas will rise further as CO2 allowances are applied at the point of fuel supply. At the same time, the European Commission has recommended that member states reduce electricity taxes and network tariffs to support electrification, a policy direction that would narrow the retail electricity cost base and strengthen the economics of heat pumps relative to both gas and hydrogen.

Synthetic liquid fuels based on hydrogen and captured CO2, such as e-methanol, carry additional cost layers: hydrogen input, CO2 feedstock at realistic capture and transport cost rates, synthesis plant capex and financing, electricity for electrolysis and conversion, and distribution and tax layers. A conservative assembly of those inputs for e-methanol produces plant gate costs well above €3 per kilogram, and when converted to energy terms that is equivalent to roughly €150 per gigajoule before distribution and value chain margins. Wholesale terminal costs and VAT or excise for road fuel usage push RFNBO liquid costs further into a range equivalent to roughly €200 to €300 per gigajoule.

When framed against conventional fossil alternatives, which rarely exceed €40 per gigajoule even after carbon pricing, the economic gap cannot be bridged without massive and persistent government intervention or quotas that force offtake regardless of cost.

At a depot electricity price of €0.15 to €0.25 per kWh, the raw energy cost for battery electric trucking is roughly €42 to €69 per GJ, but battery electric trucks convert about 85% to 90% of that energy to motion, giving an effective cost of useful energy around €47 to €81 per GJ. Diesel engines in heavy trucks typically convert only about 40% to 45% of fuel energy to motion, so even if diesel fuel costs €20 to €35 per GJ at wholesale, the effective useful energy cost is closer to €44 to €88 per GJ, while RFNBO synthetic fuels at roughly €200 per GJ translate into well over €440 per GJ of useful motion after drivetrain losses.

The cost math explains why German operators in transport are choosing electrification pathways when they are spending their own capital, per a 2025 industry survey by the Öko-Institut, following up on a similar survey from the early 2020s. A battery electric heavy truck uses electricity much more efficiently than a fuel cell truck uses hydrogen, such that even modest retail electricity prices for depot charging yield energy cost equivalents far below hydrogen fuel cell energy costs on an equivalent useful energy basis. In trucking, which the French audit and joint German-French economic advisory guidance explicitly discuss, electrification has a clear cost advantage once charging infrastructure and fleet procurement costs are included. These demand signals, where they exist, are powerful evidence that delivered economics rather than policy narratives are shaping adoption. When freight operators plan fleets around battery electric drivetrains and governments see low utilization of hydrogen pilots, it reflects a structural reality rather than a temporary market distortion.

Hydrogen rail in Germany and across Europe has shifted from flagship demonstration to retrenchment as operating realities have undercut early optimism. Alstom’s Coradia iLint trains were promoted as clean diesel replacements on non-electrified regional lines, but several German states reported reliability issues, fuel supply constraints, and higher operating costs than projected, leading to service withdrawals and interim returns to diesel units. Hesse suspended regular hydrogen service after repeated technical problems, while other Länder have moved toward battery electric multiple units paired with selective overhead electrification. In the Netherlands, hydrogen rail tenders failed to produce economically viable bids and were canceled in favor of battery alternatives. Most tellingly, Alstom has stepped back from expanding its hydrogen rail program, effectively exiting the market beyond fulfilling existing commitments as orders proved limited and cost competitiveness remained elusive. When operators evaluate lifecycle cost, infrastructure complexity, and energy efficiency, battery solutions increasingly prevail, reinforcing the broader pattern that hydrogen in transport struggles to sustain adoption without sustained subsidy or mandate support.

The ambitions embedded in both national hydrogen strategies assumed not only rapid scale-up of electrolysis capacity but also anchor industrial and power sector demand that would justify early infrastructure investments such as dedicated pipelines. In Germany, projected domestic electrolysis capacity of 10 gigawatts by 2030 was missed by a wide margin, with only a tiny fraction installed by 2025 and revised projections significantly lower for 2030. On the import side, national projections implied import demand that would absorb a bewildering share of global green hydrogen production capacity currently under development.

Germany has begun commissioning segments of its hydrogen backbone network even though there are no large-scale domestic suppliers feeding it and no firm, contracted customers drawing significant volumes from it. Pressurizing pipelines without synchronized production and offtake turns what was framed as optional future capacity into active infrastructure carrying operating costs and financing risk. With electrolyzer build-out lagging targets and industrial demand for green hydrogen far below early projections, the backbone risks becoming a low-utilization asset that depends on regulated tariffs or taxpayer support rather than molecule flows to justify its existence.

When audited against real progress, these projections look implausible rather than ambitious. Sunk costs in pipelines without corresponding signed supply contracts or committed customers do not validate the strategy; they represent misalignment between planning and market reality. Once pipeline segments are in service and pressurized, they incur operating costs, safety requirements, and financing liabilities that must be honored irrespective of whether molecules ever flow, and that changes the evaluation metric from optional latent capacity to active, revenue dependent infrastructure.

The collective advice from French and German auditors and economic advisory councils thus points toward a narrower, more pragmatic role for hydrogen: specific industrial feedstock use cases where electrification is not feasible, and some limited long-distance marine or aviation applications where battery solutions are impractical and where synthetic fuels might be mandated at high blend rates in any case. It does not support broad hydrogen mandates for road freight or general energy substitution.

By contrast, continued insistence on expanding quotas and building infrastructure in the absence of credible demand and cost competitiveness amounts to a request for bailouts of bad decisions. The EU’s task should not be to rescue uneconomic assets with quotas and subsidies but to redirect support to the pathways that independent cost and adoption evidence shows are winning: electrification with grid investment, high-power charging corridors, and targeted support for genuinely hard-to-electrify sectors. Ignoring the auditors and doubling down would not correct a market failure but would enshrine a costly detour in the energy transition that institutions on both sides of the Rhine have already recognized as unlikely to deliver on its original promises.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy

cleantechnica.com

#Germanys #Bid #Double #Hydrogen #Fuel #Targets #Ignores #Operator #Demand #Cost #Signals